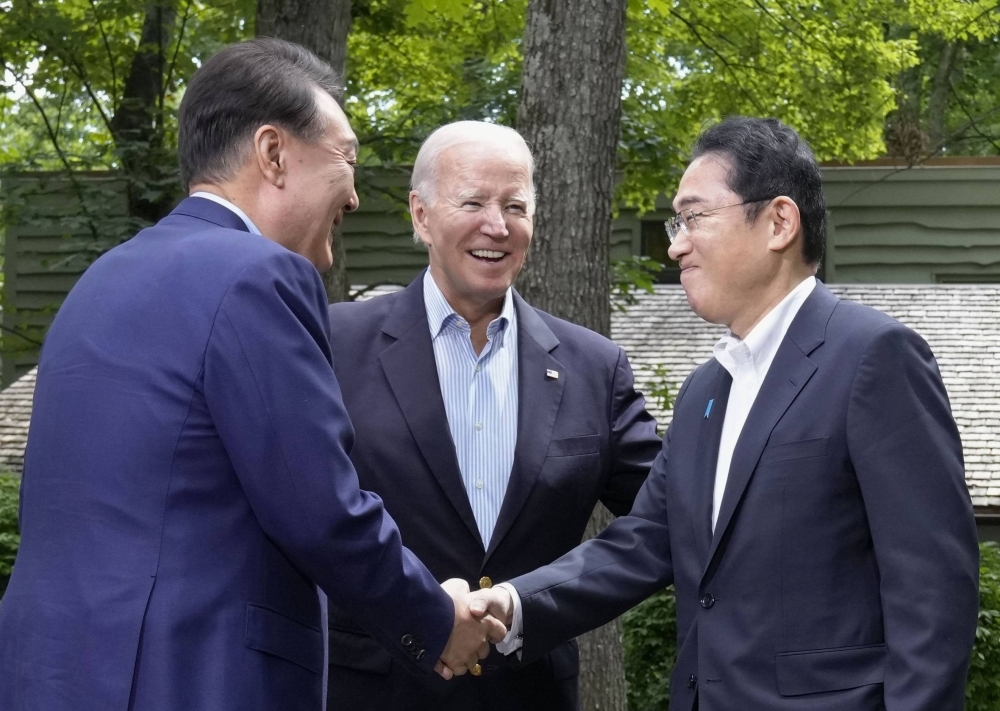

When the leaders of Japan, South Korea and the United States stood together at the rustic Camp David presidential retreat to announce “a new era” of trilateral cooperation, they were quick to offer reassurances that their historic pledge will have staying power.

Whether that will be the case remains up for debate, though a confluence of factors — including rising concerns over China’s moves near Taiwan and in the East and South China Seas, as well as alarm at the pace of North Korea’s nuclear and missile breakthroughs — could help pave the way for a durable three-way relationship.

Experts say the summit was another significant step toward deepening and expanding trilateral cooperation across a broad swath of areas as diverse as diplomacy, technology education and security.

“However, the success of the trilateral framework hinges not simply on the capacity to deal with the array of agendas, but its consistency, credibility and sustainability,” said Ryo Hinata-Yamaguchi, a project assistant professor at the University of Tokyo.

Friday’s trilateral summit at the highly symbolic venue in Maryland — traditionally reserved for historic diplomatic announcements — saw Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, South Korean leader Yoon Suk-yeol and U.S. President Joe Biden agree to meet in-person at least once a year while also dispatching Cabinet members, including their defense chiefs, top diplomats and senior economic officials, for annual trilateral meetings.

The leaders also agreed on a multiyear framework that includes annual, named, multidomain joint military exercises, which, together with a plan to share real-time missile warning data by the year’s end, “will constitute an unprecedented level of trilateral defense cooperation,” according to the White House.

But Biden and the other leaders were quick to note that the bolstered cooperation went far beyond one-off tie-ups.

“What makes today different is it actually launches a series of initiatives that are actually institutional changes in how we deal with one another — in security cooperation, economic cooperation, technology cooperation, development cooperation, consultation, exercises,” the U.S. leader told a joint news conference with Kishida and Yoon. “And all of this will create momentum, I believe, year by year, month by month, to make the relationship stronger and more certain to remain ... in place.”

Biden showered the two Asian leaders with praise for their “political courage” in mending the bilateral relationship between Tokyo and Seoul, taking it to fresh heights after years of frosty ties and setting the stage for the three leaders to cement the trilateral relationship at the historic summit.

The scene, observers said, would have been almost inconceivable just a year ago, with Tokyo and Seoul entangled in a long-festering row over thorny wartime history issues related to Japan’s 1910-1945 colonization of the Korean Peninsula that spilled over into the trade arena.

“The Camp David summit is truly historic, unimaginable until now, because the Seoul-Tokyo relationship was always fraught with historical disputes miring the two legs of the triangle,” said Duyeon Kim, an adjunct senior fellow with the Indo-Pacific Security Program at the Center for a New American Security think tank.

But, faced with a number of overlapping security concerns, Kishida, Yoon and Biden highlighted their consensus on the critical need to re-energize trilateral cooperation.

“At the moment, the free and open international order, based on the rule of law, is in crisis,” Kishida said, noting Russia’s war in Ukraine, ongoing attempts to change the status quo by force in the East and South China Seas and North Korea’s growing nuclear and missile threat.

“Under such circumstances, to make our trilateral strategic collaboration blossom and bloom is only logical and almost inevitable and is required in this era,” he said.

As a first step, the three leaders unveiled the Camp David Principles — a broad brush document in which they committed to “shared principles” to guide the partnership “for years to come” as they embarked on a “new chapter together.”

These principles included a focus on “a free and open Indo-Pacific based on a respect for international law, shared norms, and common values,” while strongly opposing “any unilateral attempts to change the status quo by force or coercion” – the latter being widely seen as a thinly veiled jab at China.

While the three leaders had no discernable issues with agreeing on measures to deter North Korea, sensitivities over how best to tackle the challenge of China’s growing assertiveness and concerns over its military modernization were more evident.

Although Sino-U.S. ties have plummeted amid their intense rivalry, Japan and South Korea have sought to strike a balance with Beijing, a key trade partner, and their mutual ally Washington.

Japan has taken a more aggressive stance, largely following U.S. initiatives to impose controls on the export of critical semiconductors to China as part of a bid to curb Beijing’s access to advanced technology that could be used in its military modernization. But it has also looked to stabilize ties with China, with Kishida on Friday emphasizing his intention to maintain “positive momentum” toward improving bilateral relations.

South Korea — the world’s No. 2 producer of chips and one of China’s biggest partners in the industry — has largely held out on joining the U.S. export controls to avoid antagonizing Beijing. But it has also released its first ever Indo-Pacific Strategy, which aligns with the U.S. vision of maintaining the rules-based international order, while Yoon sparked an angry reaction in Beijing after he emphasized that increased tensions around democratic Taiwan were due to attempts to change the status quo by force — something he opposes.

Still, the leaders did take another step closer to the U.S. position on China, with the three using a separate joint summit statement to call the Asian powerhouse out over its “dangerous and aggressive behavior supporting unlawful maritime claims” in the South China Sea and its moves near Taiwan, which Beijing views as a renegade province that must be unified with the mainland, by force if necessary.

“Peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait,” they said, is “an indispensable element of security and prosperity in the international community.”

On China, Lauren Gilbert, an expert on South Korea-Japan-U.S. ties with the Atlantic Council think tank’s Indo-Pacific Security Initiative, said that despite some misgivings about explicitly naming China, the three leaders ultimately crafted a clear, if subtle, message “that South Korea and Japan will not sit idly by should Beijing actively increase its economic and maritime aggressions.”

Although Biden said Friday that, while the world’s No. 2 economy was discussed at the summit, the meeting “was not about China,” that assertion is unlikely to hold water in Beijing.

Highlighting this, the country used its state-run media apparatus to convey its suspicions that the summit was intended to rein in China’s ambitions, part of what Chinese leader Xi Jinping has called the “all-around containment, encirclement and suppression of China.”

“It is appropriate to say that the Camp David summit is possibly a starting shot for a new cold war," Lu Chao, an expert on Korean Peninsula issues with the Liaoning Academy of Social Sciences, told the Global Times newspaper on Friday.

Beijing has repeatedly claimed that closer U.S.-Japan-South Korea ties amount to the creation of a “mini-NATO” in Asia, a contention vociferously denied by the three partners.

Asked Friday if the ultimate goal would be a formal trilateral alliance and a mutual defense pact, U.S. national security adviser Jake Sullivan, who accompanied Biden to Camp David, said Washington had “not set that as an explicit goal.”

“We have not set an endpoint of a formal trilateral alliance,” Sullivan said, noting the “strong and deep” bilateral alliances with both Japan and South Korea. “We would like to see them continue to strengthen their cooperation and for this three-way cooperation to get deeper and more institutionalized.”

But while deeper trilateral cooperation would be far from a formal alliance, the summit appeared to leave the door open for Tokyo, Seoul and Washington to get as close to that as would be palatable.

Indeed, amid concerns over China’s designs on Taiwan, one of the most important agreements to emerge from the summit was the three leaders’ decision to create a hotline for sharing information and coordinating responses to “regional challenges, provocations, and threats” affecting their countries’ “collective interests and security.”

“Critically, we've all committed to swiftly consult with each other in response to threats to any one of our countries from whatever source that occurs,” Biden told Friday’s news conference. “That means we'll have a hotline to share information and coordinate our responses whenever there is a crisis in the region, or affecting any one of our countries.”

Yoon, who analysts say is concerned that North Korea could seek to take advantage of a U.S.-China conflict over Taiwan by making its own move on the Korean Peninsula, was even more direct on what this entailed.

“Any provocations or attacks against any one of our three countries will trigger a decision-making process of this trilateral framework, and our solidarity will become even stronger,” the South Korean president said.

But before that consultation mechanism even gets off the ground, the framework will likely first have to prove that it is built to last beyond the terms of the three leaders. Ties between Tokyo and Seoul have a tendency to ebb and flow with changes in leadership, while the possibility of former U.S. President Donald Trump, a skeptic of the U.S. alliance system, winning the 2024 presidential election has also left some wondering if he would abide by the deals reached at the summit

“The biggest challenge will be having their respective governments implement the agreements proactively even when diplomatic spats arise between South Korea and Japan,” the Center for a New American Security’s Kim said.

“If an ultraleftist South Korean president and an ultra-rightwing Japanese leader are elected in their next cycles, or even if Trump or someone like him wins in the U.S., then any one of them could derail all the meaningful, hard work the three countries are putting in right now.”

culled from Japan Times